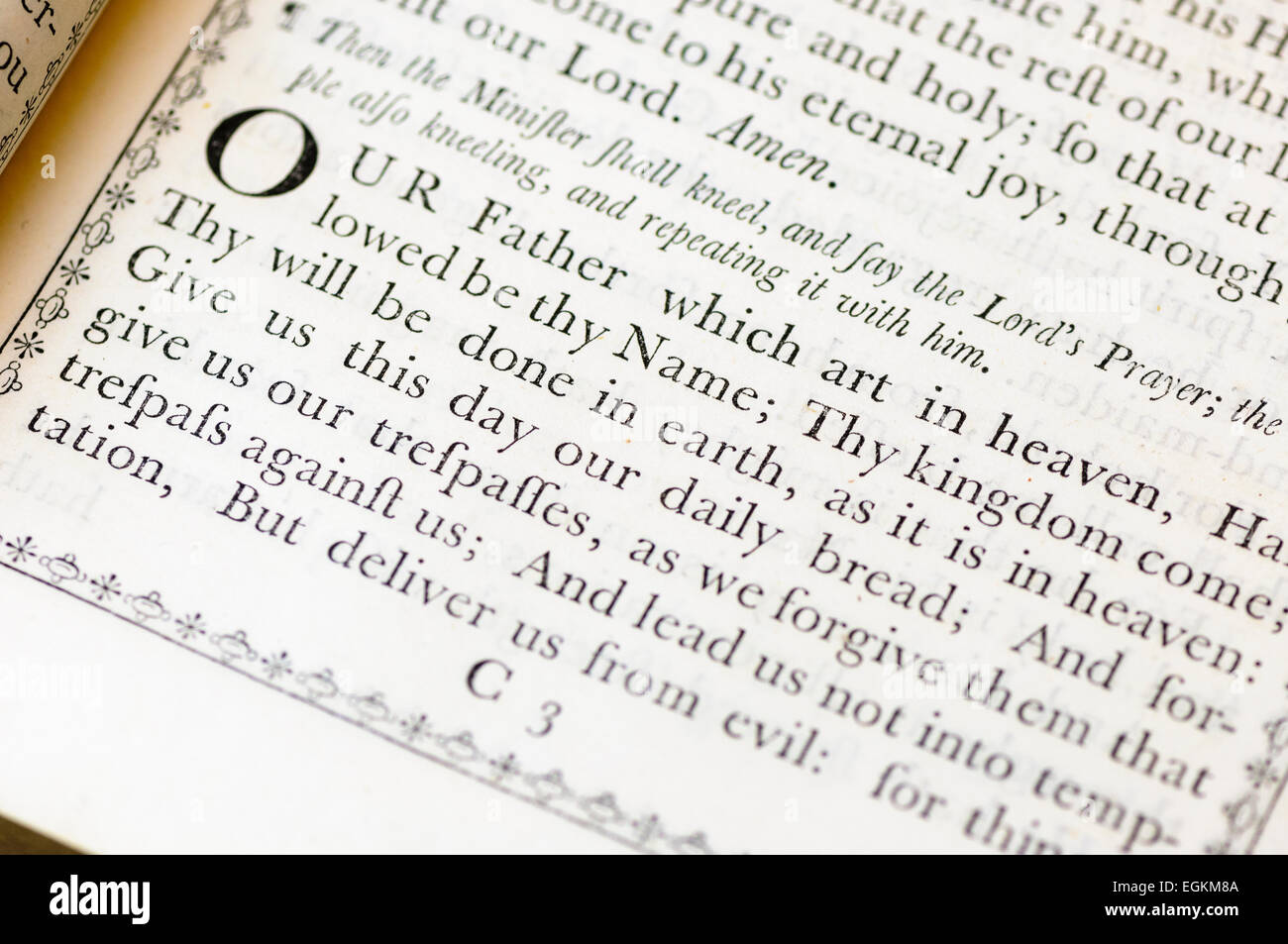

1552 Book of Common PrayerThomas Cranmer et alSkillfully crafted in wonderfully emotive language, Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury established the first doctrinal and liturgical structures of the reformed Church of England. The deep thoughts revealed truly bring prayer to life.

And so a consultation of bishops met and produced the first Book of Common Prayer. It is generally assumed that this book is largely the work of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer ( pictured below ), but, as no records of the development of the prayer book exist, this cannot be definitively determined. Hearts of iron 4 portraits for sale.

The Book of Common Prayer contains forms of service for daily and Sunday worship, morning and 1552 Book of Common PrayerThomas Cranmer et alSkillfully crafted in wonderfully emotive language, Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury established the first doctrinal and liturgical structures of the reformed Church of England. The deep thoughts revealed truly bring prayer to life. The Book of Common Prayer contains forms of service for daily and Sunday worship, morning and evening prayer, the Litany, Holy Communion, baptism, confirmation, marriage, and funerals.

Don Whitney Praying The Bible

A major revision published in 1662 is used today in 50 different countries and in over 150 different languages! A solid starting point for daily devotion!1662 Book of Common PrayerThe Standard for Anglican Worship by Thomas Cranmer et alA verbal masterpiece, in ’archaic’ but elegant style. A living testament to the English Reformation, Cranmer’s work is a milestone in church history, capturing the essence of the English language and culture, chronicling its enduring achievements. The mechanism of prayer does not interfere with the spirit or intent of prayer.

This warm and wonderful daily companion of liturgical prayer has spiritually nourished Christians over the centuries. An Anglican gift to the world, it continues to guide worship and stimulate spiritual growth. A blessing indeed!

The Telegraph Thomas Cranmer and the Book of Common Prayer The first entry in the 'Common Saints' series, on the man and book that set the course for Anglican doctrine.Posted July 9th, 2014 by & filed under.The philosopher Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy once remarked that “experiences of the first order, of the first rank, are not realized through the eye.” What he meant was that auditory experiences—sound, hearing, music, words, language itself—provide access to an order of reality that goes much deeper than that afforded by sight. The visual realm is one of measurable objects, empirical facts. It is the flat abode of experimental science. The aural realm, in contrast, is one of meaning, mystery, and faith. It gives duration and depth to the environment. It breaks in upon the world, suggesting something beyond the world. It cannot be seen; it must be believed.Obviously this schema resonates strongly with religion, and with Christianity in particular.

“In the beginning was the Word”; “Go into all the world and proclaim the gospel to the whole creation”; “Faith comes through hearing.” Although I happen to believe that images remain an indelible part of Christianity (after all, the Word did become flesh), it is undoubtedly a religion of the word. The word is God’s chosen medium of communication with us, and it is our primary form of communication with others.This lengthy and rather abstract introduction is all to say that words are especially important for Anglicans. Our liturgies and lives are shaped (and have been shaped, for hundreds of years) by the remarkable words of the Book of Common Prayer. This text—produced at the height of the English Reformation with the intent of unifying England in a common, vernacular liturgy—is the doing of, the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556).

Despite being a product of the print era, which made it possible for one to read texts alone and apart from communities, as a liturgical text the book is a communal object, meant to be spoken aloud in the presence of and with others in worship. It made worship more congregational, giving the laity more to say than they had in years past, while retaining a structure similar to that of the Catholic Mass.As anyone who has experienced an Anglican service knows, speaking the beautiful words of this particular liturgy with others is an incredibly powerful act of worship. Part of this power comes from the poetic quality of the words themselves. Has pointed out that the Book of Common Prayer’s language was carefully sculpted for reading aloud. Cranmer compiled and adapted components from the medieval Latin liturgy, often infusing them with poetic structures borrowed from biblical Hebrew. The prayers have a certain rhythm and parallelism to them; their particular cadences roll off the tongue and produce flowing rivers of sound:Almighty God, unto whom all hearts be open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid; Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of thy Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy holy Name; through Christ our Lord.

Amen.These prayers have. Although the Book of Common Prayer has undergone numerous revisions and changes over the years, some of our best-loved phrases are found within its covers. Whenever we hear “to have and to hold from this day forward, for better for worse” at a wedding; “ashes to ashes, dust to dust” at a funeral; or “moveable feast” and “children of men” in titles of art, we are hearing the Book of Common Prayer.The Book of Common Prayer’s achievements, however, go far beyond the literary, and have to do with content as well as form. Theologically, Cranmer’s book is without a doubt a child of the Reformation. Cranmer himself was embroiled within the tumults of the English Reformation, living through the religiously fraught reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, and the Catholic Mary I, under whom he was finally executed for treason and heresy.

He had a reputation for being a little weak-willed and inconsistent, at one point recanting his Protestant beliefs and then renouncing his recantations. But despite (or perhaps because of) a hectic political life, Cranmer held a robust theology, which he infused into the Book of Common Prayer.The Anglican liturgy is saturated with Scripture and reflects a Protestant sensibility on issues like the role of images in worship and the veneration of saints.

Yet it also navigates ground between Catholicism and radical Protestantism, a “middle way” that has remained a distinctive feature of the Anglican church.In keeping with the spirit of the Reformation, one of its most prominent features is its emphasis on humanity’s sinfulness. In the General Confession portion of the Morning Prayer, the people respond to the reality of sin with the following:Almighty and most merciful Father; We have erred, and strayed from thy ways like lost sheep.

We have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts. We have offended against thy holy laws. We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; And we have done those things which we ought not to have done; And there is no health in us. But thou, O Lord, have mercy upon us, miserable offenders.But this emphasis on sinfulness does not amount to total depravity; the Book of Common Prayer also consoles and comforts, reminding us that God is guiding us on His path. In accordance with our free will and assent, we are to answer God’s call and meet Him in His work:O Almighty Lord, and everlasting God, vouchsafe, we beseech thee, to direct, sanctify, and govern, both our hearts and bodies, in the ways of thy laws, and in the works of thy commandments; that through thy most mighty protection, both here and ever, we may be preserved in body and soul; through our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ.

Amen.Cranmer’s views on the Eucharist, the central act of Christian worship, are perhaps the most difficult to tease out. What is certain is that he rejected the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation as well as Luther’s own view of the sacrament.

Both of these positions claim that Christ becomes physically present at a certain moment in the liturgy.